The ALD Aesthetic

Aimé Leon Dore changed how menswear markets, but a backlash is growing.

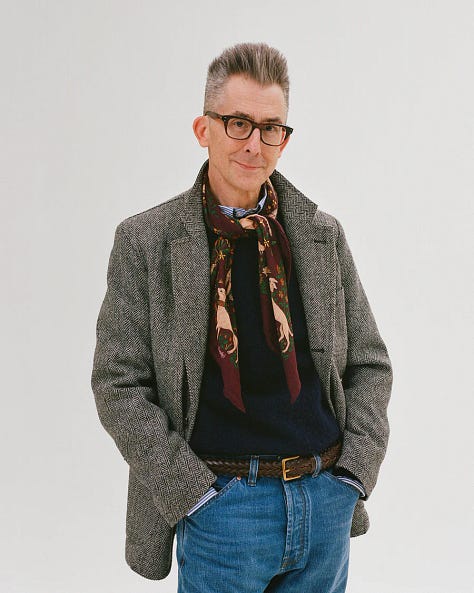

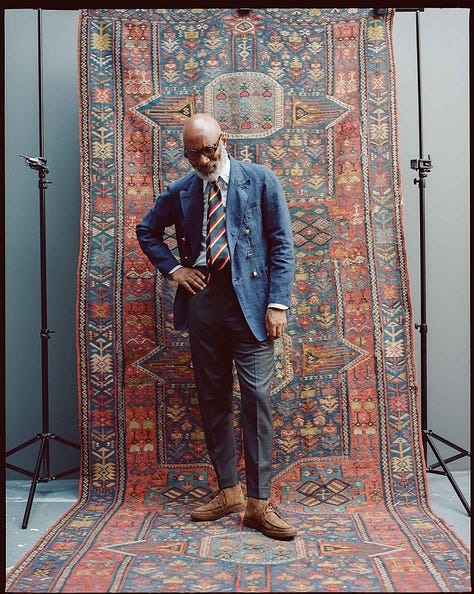

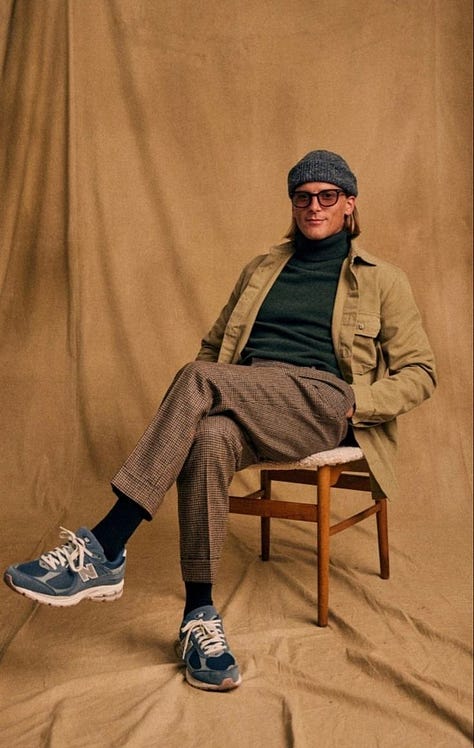

Have you seen these men?

Of course you have, likely many times appearing in the seasonal campaigns for multiple brands. In fact, casting “real guys,” marketing argot for hiring non-models, has become so commonplace in menswear that GQ’s Jason Diamond even coined a term for it earlier this year, the “Homie Look Book” (this came after—surprise—Diamond was featured in one). For that you can thank Aimé Leon Dore, the New York-based streetwear-turned-luxury brand that went from menswear insider darling to LVMH investment (Alexandre Arnault sits on their board) in just a few short years. Aimé Leon Dore, or ALD to fans, hit on an algorithmically perfect combination of impeccable styling, Ralph Lauren-like world building, and IYKYK campaigns stuffed with influencer Easter eggs.

The clothes themselves felt engineered to appeal to a Millennial customer with their mix of ‘90s nostalgia and social feed friendly colors and fabrications. As a gushing 2023 profile from the Times’s Jon Caramanica put it, “[ALD’s] garments are swarthy and a little sensual, displaying a clear affection for Ralph Lauren but also for how hip-hop appropriated Ralph Lauren in the 1990s.” The brand was beautifully executed, which meant it quickly found its way onto every Creative Director’s mood board. Working in the apparel industry during the pandemic years it felt impossible to escape ALD’s influence on how brands aspired to creatively market themselves, and that is how I met Nick Tazza.

You’ve probably never heard of Nick—unless you’re an Algernon Cadwallader fan—and he prefers it that way. But you should, since not only is he a meticulous, passionate, and inventive creative director and designer, he’s also largely responsible for the visual identity of ALD. That now iconic logo? Nick hand drew it. The ALD website? Built by Nick. The original flagship store on Mulberry Street that became a downtown destination? Nick and his wife, Christine, designed it through their agency, Fork Spoon. Nick is effusive in his praise for ALD founder Teddy Santis and his creative vision, describing himself himself as just a “filter,” but if ALD is a triumph of branding I think credit is due to the man who branded it.

I wanted to talk to Nick about those early days at ALD and how the visual language of the brand—call it the “ALD Aesthetic”—came together, not only in the aforementioned campaigns but also in their e-comm images (aka model shots), which are also heavily replicated across the industry. “Some of the really early genius of ALD was the juxtapositions. They would take a ratty old basketball and put it up against a white wall. That high-low juxtaposition started to treat things as objects, as art pieces. It started to make them really covetable.”

An old basketball, a mid-century stool, a Persian rug. ALD inserted recursive compositional elements to their e-comm shots, turning them from simple selling tools into mini-campaign images. It’s worth noting that the only other brand that dedicates themselves to that level of propping, stage setting, and visual minutia is Ralph Lauren. Nick brought up ALD’s “Class Of…” photo exhibit from 2015, in which artist Andrew Jacobs took “objects and product which are nostalgic of an era that has inspired” the brand and framed them within what looked like the white cube of a gallery. But what was totemic in 2015 started to look a lot like a brand “starter pack” (more on that in a bit) by 2021 when ALD offered the first of six, thus far, curated collections of vintage pieces, like Navajo blankets, Jordan 1’s, Raekwon LPs, and rusty Krylon cans (for $150).

To get a better understanding of how the growing success of the ALD aesthetic was being absorbed and interpreted across menswear, I also reached out to creative producer and stylist, Hilmar Skagfield. “I just really loved what ALD was doing at the time because it was encapsulating two things, which is real community—or the perceived sense of it—and a very articulated stylistic language,” he told me. As a core member of Billy Reid’s team for many years, and a thoughtful observer of fashion, Hilmar is better positioned than most to speak ALD’s impact on creative output. “You saw these worlds that were starting to be built,” he explained, “that used a lot of ALD’s visual language. How they would style their flats and how they would style product shots. And then there was various groups that started to really do that kind of indoor photography where it's just straight to camera and a good stylist on top of that.”

Hilmar brought up the great point that by 2019, much of menswear was in thrall to basics brands like Everlane and Buck Mason, but ALD’s tack was, in his words, “Hey, forget the basics. Let's go for this thing.” To do so required a visual approach that took marketing images out of their typical lifestyle or product lanes and elevated them to—Hilmar’s words again—”the language of portraiture.”

That sense of “real community” that Hilmar brought up was also echoed by Nick as a critical component of ALD’s achievement. ”What they did, knowingly or unknowingly, is they built an honest brand by validating it through dope friends,” observed Nick. “And because they're invested in that brand, not on like a veneer social media level. [ALD is] not paying anybody to be a part of that brand.” Paid or not, it was an incredible feat of casting, and menswear ouroboros, as the characters that populated ALD’s campaigns were the same ones photographing menswear, podcasting about menswear, consulting to menswear brands, and even designing the clothes themselves. It was the entire ecosystem in one lookbook, each one an influencer with their own reach. No wonder so many other brands cribbed the play sheet.

“You wanna build a brand that people wanna be invested in. And they helped people invest in it. It's genius marketing to this day,” said Nick.

Last spring, Deez Links dropped an anonymous polemic entitled “I hate menswear,” which colorfully described the current state as “a spindly glory hole that, if you dare jam your dick in, tickles for a second but mostly makes you feel broke and sad.” It was profane, hilarious, and crucially, the first time I saw anyone openly turn on ALD.

The worst offender of this generation is, by far, the New York City brand Aimé Leon Dore, which is basically fast fashion with Supreme prices. The fact that ALD—a brand whose whole cinematic universe can be distilled down to “What if we dressed like 9/11 never happened?”—is at the forefront of menswear says a lot about how dire things have gotten and how bereft we are of actual creativity. It’s fine to build a clothing brand rooted in personal geography. (See: Our Legacy, 18 East, Story MFG.) But nostalgia is easy, and, by definition, derivative. ALD is like a Ghostbusters reboot dressed up in DEI language. It purports to represent all the right things—good taste, downtown cool, an aspirational lifestyle—but if you look under the cortado lid, you’ll find it’s mostly empty. You’re just an uppity city boy with a large vinyl collection and pictures of sourdough on the grid.

It was a few months before ALD would drop a capsule collection with Porsche—aka menswear’s most cliched side interest—and right around the time I started to notice Aimé hats on “Poppy’s moms.” Something about the ALD vibe had shifted, from the aforementioned “downtown cool” to Ralph for crypto bros. Then, last summer, I came across a post by Thread Space entitled, “The Issue With Modern Day Lookbooks,” that drew a comparison between pre-internet catalogs, with their outdoorsy lifestyle images, and ALD’s fit pic approach, which the author laments was now being emulated by subreddit users.

The clothes are ironed, they aren’t dirty or worn; they’re crispy and clean and fresh out of the laundry, always. The rooms are clean and stylized with mid century modern lamps and a Virgil Abloh confutable [sic] book. There’s a nice chair with a nice blanket folded over it. It’s your room, but it’s also the ALD lookbook.

And it makes sense, doesn’t it? The same way that we used to want to have lives that reflected the J Crew or Ralph Lauren catalogs, now we want a life that reflects the Aime Leon Dore lookbook.

The ALD aesthetic had become so widely ingrained, and so easily replicated, in menswear that even consumers were styling themselves and their lives to reflect it. It had in essence become, as the Deez Links post original wrote, “a starter pack.” “This marketing playbook, popularised by brands like Aimé Leon Dore and followed by many others, has led to a lack of creativity and experimentation,” declared Business of Fashion this fall. The title of the piece was, tellingly, “Why Does Menswear All Look the Same?” In it, BoF reporter Malique Morris is quoted as saying, “Everything is good and nothing is great. So if everyone can dress well, then no one is actually cool.”

I asked both Nick and Hilmar what they thought of that. For Nick, it was a symptom of the “visual lameness” he saw across the industry, the fault of both lazy creatives and performance marketing’s content churn. “We're just in this perpetual state of reference homogeny, algorithm homogeny, cultural homogeny,” Nick responded. “Why does every brand look like ALD? It’s because they're the cultural center point right now and everyone's in a feedback loop.”

For Hilmar, it was something a bit more philosophical. “If I asked you, what is cool, what does it mean to be cool? How would you define that right now?” He went on to explain that during his undergrad studies of the philosophy of fashion he came up with a working definition: secret knowledge around how to really live. Maybe that’s what the ALD aesthetic was really about, telegraphing the secret knowledge of how Teddy Santis and friends lived, worked, played, ate, and dressed.

But now, the secret is out.

Ralph was once quoted as saying "There is a way of living that has a certain grace and beauty. It is not a constant race for what is next, rather an appreciation of that which has come before." Perhaps 9/11 hit the pause button on that "cinematic universe" and the homie lookbook is the visual evolution of the homie cookbook, but ALD will continue to do just fine as a more commercially viable Rubato (or any other highbrow but non-scalable brand) that the Simon Cromptons of the world champion so dearly. Great piece as ever MBD.

I find that last bit quite profound -- an aesthetic is cool when it signals secret knowledge around how to really live. The secret being out ruins its coolness because it ceases to be a signal of that lifestyle.

Great essay, have been thinking about it on and off for the past few weeks :)