How Ivy Ends

Menswear's favorite look has been going hard for a century. How much longer can it last?

The new spring issue of Uniqlo’s in-house magazine, LifeWear, opens with a breezy feature entitled, “Good Morning, New York City.” In it, a cadre of young models sip coffee at diners and cafes, intently cross streets, and lean on all manner of sun dappled city fixtures. Their outfits are both polished and casual, perfectly styled yet nonchalantly assembled. Dark loafers contrast against white socks, shirts in soft pinks and blues peak out from under navy blazers, sweaters encircle necks and waists, and chinos seems imperative. The subtitle is “Eight New Yorkers seize the day wearing preppy springtime styles,” as if they needed to spell it out. But you know what they’re really talking about: Ivy style.

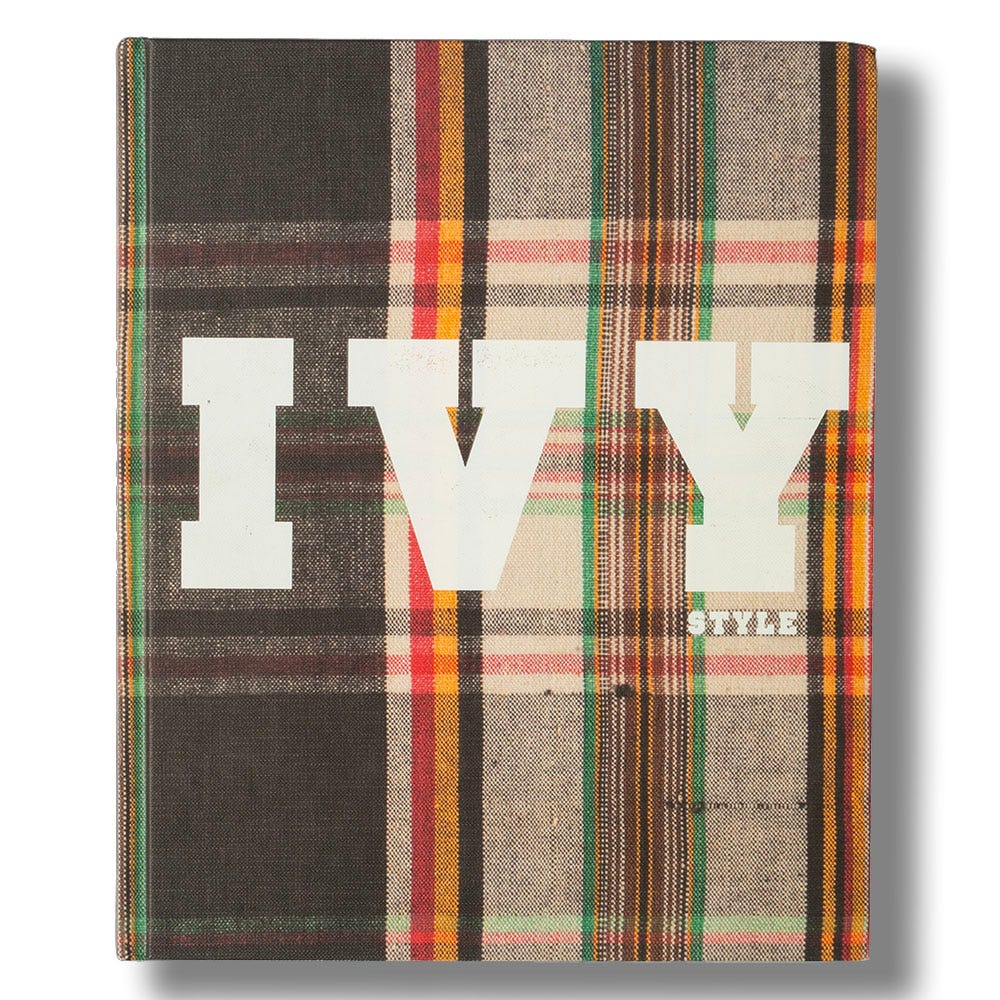

Ivy League style is the trend menswear always returns to, a modern day origin story to endlessly debate and dissect. It also serves as menswear’s most durable folk tradition and marketing tool. Nearly a century after its creation, Ivy style still inspires books, blogs, podcasts, museum exhibitions, fashion spreads, Instagram accounts, and yes, more than few Substacks. It’s even birthed a cottage industry of specialized Ivy experts, like W. David Marx (Japanese Ivy), Jason Jules (Black Ivy), and Avery Trufelman (Grand Unified Theory of Ivy).

But why? Why in 2025 do we still pore over “Take Ivy” like a Talmudic scholar, debate which brand has achieved the Oxford collar roll Platonic ideal, and wonder if Brooks Brothers will ever see a return to form? The answer is likely as simple as, it’s fun (for us) and it makes money (for brands). And if that was all I came here to do I could stop now, but it’s not. I have no new insights to add to the vast body of Ivy scholarship and in matters of Ivy’s beginnings and evolution I humbly defer to the experts. Instead, I want to know what the next hundred years looks like for Ivy and how many more times menswear can keep going back to that well. I want to know how Ivy ends.

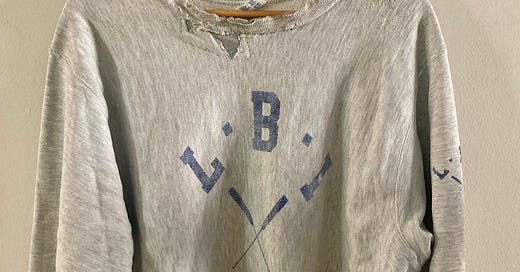

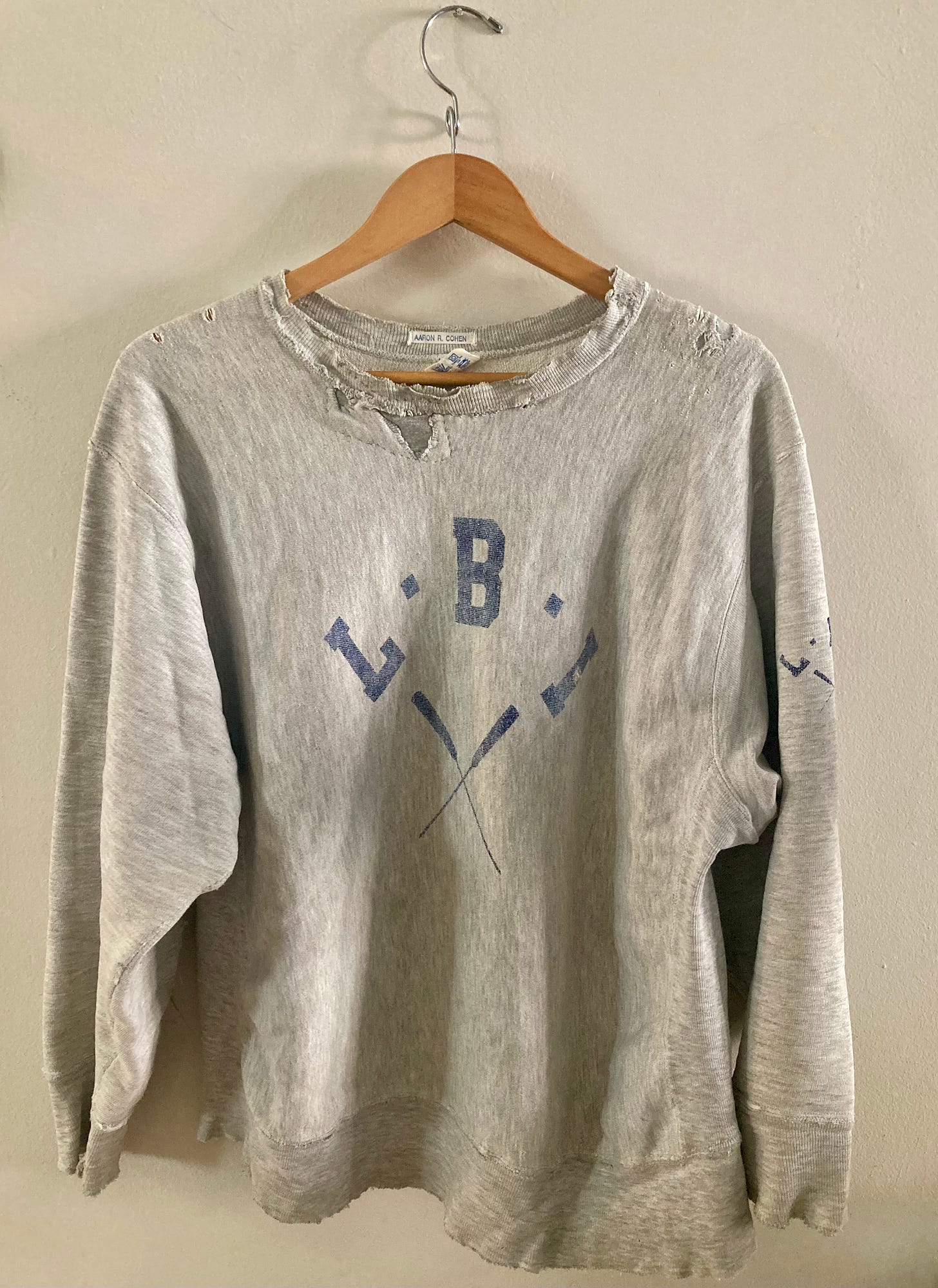

The legend of Ivy League style goes something like this: on the campus of Princeton University—and maybe Yale too—in the 1930s a confluence of eastern establishment culture and geographic isolation led to the creation of a new, purposefully casual way of dressing that incorporated British countryside fabrics and styles with the American invention of the sack suit and the novel introduction of athletic wear. Critically, the look was as much about the “how” as the “what,” or as Ivy-Style.com put it in their 2020 magnum opus post on the subject:

The Ivy League Look was as much about styling as the ingredients. And while the ingredients were relatively fixed and admitted new items slowly, the styling came from the campus and was always in a state of flux.

This youth driven trend caught the attention of the fashion industry, which in turn fueled it to the point where, by the 1950s, it was the dominant style. This continued until the counterculture movement and the 1970s, when Ivy receded, only to reemerge in the 1980s as the preppy look. (I should note here that while I’m fully aware that differences exist between the two, preppy and Ivy are inextricably linked—”Ivy on vacation” is the best description I ever heard of preppy—and most importantly are synonymous in the majority of peoples’ minds. Let’s face it, only menswear heads use “Ivy style.”)

Today, the Ivy look lives on at its historic retailers, Brooks Brothers and J. Press, continues to be the foundation of Ralph Lauren’s global luxury empire, and perennially inspires new collections, campaigns, and brands with some take on “Ivy/preppy with a twist.”

”I think Ivy reemerged because it is the pinnacle of this minimalist, nonchalant style that is grounded in tradition, but it's also built from a bunch of garments and materials that are anchored in military and sports,” observes W. David Marx. Marx is the author of, among other books, the excellent “Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style” and is something of menswear’s resident scholar. Because of the pervasiveness of Ivy staples like penny loafers, Oxford shirts, and chinos in the marketplace, I wanted to ask Marx if there was a vanishing point for Ivy DNA in a garment, that is, when do these things just become clothes?

“I think it's a somewhat difficult question in that, I would argue, when I was growing up in the early ‘90s they were just clothes,” he responded. “No one was like, ‘Look at this. I'm wearing an Ivy shirt.’ You were just at church and everyone's in a navy blazer and a pink polo or whatever, right? So those things became just clothes. There was no media that told you the thing you were doing was special. Now, 10 years earlier with ‘The [Official] Preppy Handbook’ that was most certainly like, here is a style that you should imitate. So there was a point in the ‘80s where the clothes weren't just clothes, they were preppy, and it was a style. And then because it died off it had to come back again. That's when, especially with this media saturated world we're in, we're pointing to it like, this is Ivy. This isn't just clothing, this is Ivy. But, a pair of Dockers, is that Ivy? I would argue, no. I think there has to be some sort of intentionality.”

I thought Marx’s comment about “intentionality” was really interesting, especially since it echoed Ivy Style’s argument about the preeminence of styling with the Ivy look. And it meant that there were two things going on: clothing could reach a level of ubiquity where it becomes divorced from its original style origins yet those could be reconstituted with a degree of thoughtful effort. There is something Gestalt-y about Ivy, but how does one identify its presence? My father’s go-to dressy look for his entire life has been a navy blazer with gold buttons, an Oxford shirt, and chinos, but not only has he never heard of Ivy style he would be downright offended if you told him he was dressing preppy. I asked Marx how to draw the line.

”I guess the main point is Dockers were never sold as an Ivy thing,” he said. “Ralph Lauren sells everything not only under the marketing of, this is anchored in American tradition, but it's designed by people who are very familiar and fluent with all those conventions. And so I do think that a pair of khakis by itself is not an Ivy League garment. A navy blazer by itself isn't, there has to be some sort of intentionality to connect it back, it could be small details, like having the hook vent on the blazer is really important. And obviously the gold buttons or some sort of nauticalness. Not to get superpretentious, but the symbolic play of fashion is that these minor details create difference and the differences are where we draw meaning.”

So if garments gain their Ivy-ness when we ascribe meaning to them, what happens when we no longer have a shared definition of what Ivy style means? “My daughter’s ‘preppy’ is not my idea of preppy — the prep of actual New England prep schools, of frayed Oxford cloth and WASPy noblesse oblige,” wrote Mireille Silcoff in a 2024 New York Times Magazine piece entitled, “Teen Subcultures Are Fading. Pity the Poor Kids.” The article, written at the height of TikTok’s “-core” trend, is broadly about how social media has unmoored subcultures from their original IRL contexts, reducing everything to a series of superficial “aesthetics” that can be cycled through at dizzying speeds. But it highlighted how, for Gen Alpha at least, the very meaning of preppy has shifted.

Then last summer,

, an excitable linguist who goes by EtymologyNerd, posted a Reel in which he analyzed this change. He pointed out that the Ralph Lauren and Brooks Brothers look has been relabeled “old preppy/money” while preppy is now defined as bright, pink fashion that, according to the Times, includes “colorful Stanley mugs, tiered pink micro-minis, bulbed makeup mirrors and Brazilian Bum Bum Creams.” Perhaps it’s a stretch to think that Ivy style in menswear could be imperiled by the linguistic choices of tween girls but Ivy has disappeared before, and were it to happen again, would future generations even know how to call it back into existence?“You can take elements of [Ivy style], tweak it, invert it, turn it upside down, and it still looks like Ivy,” says Patricia Mears, Deputy Director of The Museum at FIT. “But I think you're onto something. I think it's very clear, because what happens is through enough cycles, and as the generations change and start to embrace components, they don't have an understanding of what it looked like originally.”

Mears staged the 2012 exhibition “Ivy Style,” a survey of the look’s origins and global influence, and contributed essays to its companion book, “Ivy Style: Radical Conformists.” She pointed out that streetwear has been the only major challenge to Ivy style in the last 50 years, and even that incorporates Ivy elements, which are so ingrained in menswear at this point that they would be difficult to completely erase. She also noted that at Ivy’s inception it was a truly radical way for men to dress, and that we’re not likely to experience anything equally revolutionary today.

What Mears is seeing today at FIT is a generation of students who don’t care about fit or craftsmanship or any contextualizing history. To them, Ivy style garments are just one ingredient in a vast stylistic soup that serves their need for both comfort and mercurialness. “It looks like they're experimenting almost on a daily basis,” Mears tells me. “It's like their wardrobe is a petri dish…what bacteria will bloom today?”

In the mid-20th century, the Ivy League look was a groundbreaking exercise that took certain garments, with specific details and combined them in an intentional way to create an entirely new menswear vocabulary. 100 years later those variables remain, what has changed is the experiment itself. What that will yield is anyone’s guess, and I’m terrible at predictions, but it’s clear that younger generations’ goals aren’t the same. Their idea of Ivy (or preppy, or “old preppy”) isn’t rooted in class and tradition, and it doesn’t share the same values, especially aspiration and community. Without those, what is Ivy League style, and how does it live on?

”It'll live on,” Mears assures me, “it just will just be something so different we may not even recognize it.”

“”Ivy on vacation” is the best description I ever heard of preppy” thank you for bringing this to my attention, I will never struggle to describe preppy again.

Here's a scan of the original Japanese book: https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/xf1zvp1j01czp4rgku7cp/Take-Ivy.pdf